While equities may offer higher returns, bonds are there to be a portfolio stabiliser, especially during economic downturns.

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving investment landscape, the quest for diversification and risk management has never been more critical. While equities and derivatives often capture the headlines, bonds – a somewhat understated asset class – play an essential role in achieving these objectives. This article aims to demystify some of the bond elements, such as their mechanics.

What are bonds?

Bonds are debt instruments that serve as the cornerstone of the financial markets. When you purchase a bond, you’re essentially extending a loan to the issuer – typically a government, a corporation, or a local authority. In return, you are entitled to periodic interest payments, known as “coupon payments”, along with the repayment of the principal amount when the bond reaches maturity.

Mechanics of coupon payments: An in-depth look

Coupon payments are essentially the interest a bondholder receives for holding the bond until its maturity (or while the investor holds the instrument prior to selling). These payments occur at regular intervals – usually semi-annually, annually, or biennially. Understanding the frequency and rate of these payments can help you predict the income you will derive from your bond investments.

Example: Let’s say you invest $10 000 in a 10-year bond offering an annual coupon rate of 3%. You would receive $300 annually for 10 years, culminating in the return of your original $10 000 investment at the end of the term.

Sizing up the global bond market and the sheer scale: Bond market vs global equity markets

To grasp the enormity of the bond market, one must contrast it with its often more publicised counterpart – the global equity market. As of 2022, the global bond market was valued at an astonishing $133 trillion, overshadowing the $98 trillion valuation of the global equity market. Thus, the bond market is roughly 36% larger than the global equity market, underscoring its significance as an asset class that provides depth, liquidity, and opportunities for hedging and diversification.

Factors that impact bond prices

Bond pricing is a complex process influenced by multiple variables:

- Interest rates The primary determinant affecting both coupon payments and market value.

- Creditworthiness: Ratings from reputable agencies like Moody’s or S&P can heavily influence pricing.

- Economic indicators: Inflation rates, GDP growth, and employment statistics can also sway bond prices.

The dual forces: Inflation and interest rates

Inflation is generally considered bad for bonds due to its impact on the purchasing power of future fixed coupon payments and the principal repayment at maturity. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of money over time. If the inflation rate is higher than the yield on a bond, the future coupon payments and principal repayment received from the bond may have less purchasing power when received. This means that even though the bond pays a fixed amount, it may not be able to buy as much in the future. Looking at it from a historical perspective, during the high-inflation era of the 1970s, long-term US government bonds yielded negative actual returns, losing investors an average of 2% per year.

In response to inflation, central banks may raise interest rates to control it (sound familiar?). When interest rates rise, bond prices typically fall. This is because newly issued bonds will offer higher yields, making existing bonds with lower fixed yields less attractive to investors. As a result, the value of existing bonds in the market decreases, which can lead to capital losses if the bonds are sold before maturity.

The bond-interest rate paradox and the inverse relationship explored:

The inverse relationship that bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions is more than financial folklore – it is a mathematical certainty.

Example: When the US Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near-zero levels in March 2020, the price of 10-year US Treasury bonds increased by almost 10% within a month. Now that interest has increased from 0% – 5.25% in the space of 18 months, the price of 10-year US Treasury bonds decreased by almost 20% during this period.

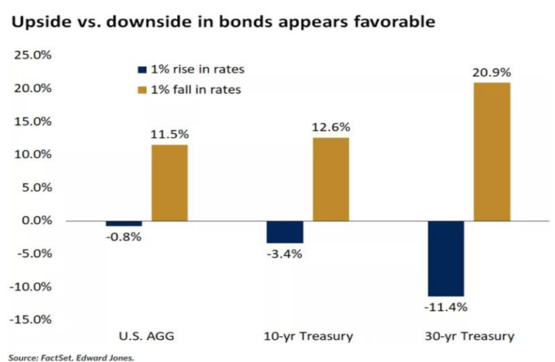

The graph below shows that yields are high and therefore are likely to produce high returns, making them attractive opportunities. The larger income component can better offset price declines, and because of that, a 1% decline in rates would potentially translate to a much larger upside in prices than the downside from an equivalent 1% rise in rates.

Conclusion

While equities may offer higher returns, bonds are there to be a portfolio stabiliser, especially during economic downturns. However, this has not been the case, and among all the chaos globally, bonds have acted similarly to equities.

As the quest for diversified, risk-adjusted returns continues to drive investment strategies, bonds emerge as an asset class that should not be overlooked. Understanding the intricacies of bond pricing, interest rate movements, and the destructive capabilities of inflation can empower investors to make informed decisions. We certainly allocate to global bonds within our own client portfolios and believe that when interest rates decrease, bonds will outperform.